The Waiting List, Part 1

This post is part of an educational series exploring Medicaid waivers and the challenges people with I/DD face when trying to secure Medicaid funding for home and community-based care. The Waiting List, Part 1 serves as a primer.

To live meaningful lives outside of institutional settings, many people with intellectual and developmental disabilities (I/DD) opt for home and community based services (HCBS). HCBS can include care coordination, chore assistance, home health visits, meal assistance, adult day services, respite services for family members, emergency monitoring, educational or employment support, home accessibility modifications and more.

Mosaic is dedicated to providing these services, in which the people we support can choose how they spend their days; communicate their wants, needs and goals; and live fuller lives in their communities.

In order to access HCBS, however, people with I/DD have to apply for Medicaid waivers and then wait – sometimes for years – for their number to be called.

Getting down to brass tactics, what are Medicaid waivers?

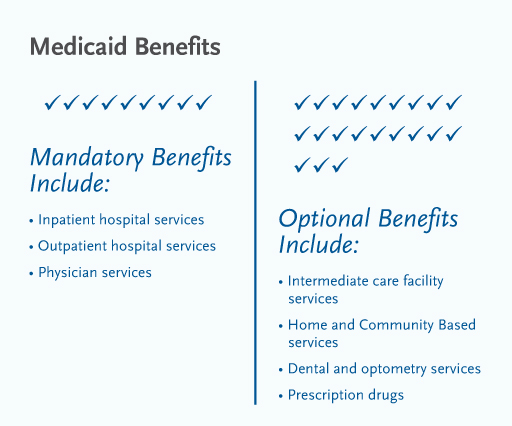

Medicaid’s standard coverage encourages institutionalization for people with I/DD instead of community-based or home-based care.

Medicaid is required to cover people in skilled nursing facilities, that is, institutions. It is not required to provide services to people with the same disabilities who live at home or on their own, or who want to be served in their home communities.

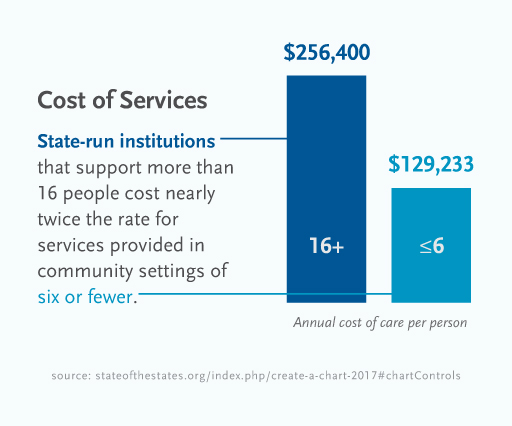

This bias toward institutionalization, as well as a growing understanding that institutional care is generally costlier than HCBS for individuals with the same level of need, led to the creation of federal Medicaid rules that allow states to establish Medicaid HCBS waiver programs.

“Basically, states have an agreement with the federal government to provide services in the community,” said Molly Kennis, Vice President of Operations at Mosaic.

While the waivers vary from state to state, they generally provide a package of medically necessary services and supports to people with disabilities whose medical and support needs are high enough to require an “institutional level of care,” but who could live in the wider community with appropriate services and supports.

If states decide to offer waiver programs, they do so by choice.

In addition to being cost-effective, Medicaid waivers represent a shift in thought about the best way to care for people with I/DD.

Though program specifics differ from state to state, one thing that is consistent is the cost difference.

While people might assume that Medicaid does not require coverage of HCBS because institutional care is cheaper, this is, on average, incorrect.

But cost savings plays second fiddle to another benefit: improved quality of life. It’s not only about being cost-effective. It’s about giving people the best possible life there is.

Nearly two decades ago, the Supreme Court recognized this truth.

Its 1999 decision in Olmstead v. L.C. held that institutional bias was not only an unjust segregation of people with disabilities from the larger community, but “confinement in an institution severely diminishes the everyday life activities of individuals, including family relations, social contacts, work options, economic independence, educational advancement, and cultural enrichment.”

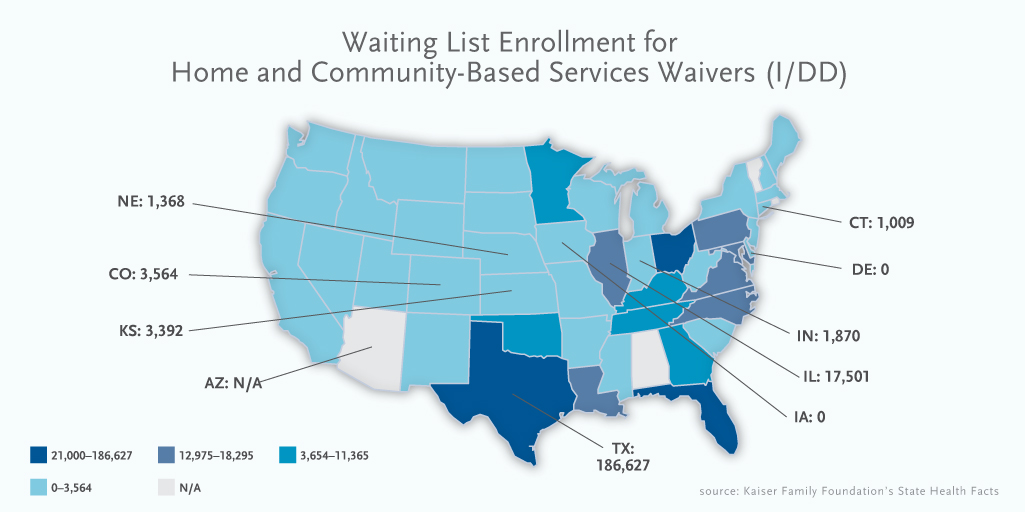

As the demand for waivers is greater than the supply, waiting lists rule the day.

In almost every state that offers an HCBS waiver program, there is more demand for waiver slots than there are slots available. States respond by maintaining a “waiting list” of people who are eligible for the program.

The list can be maintained on a first come, first served basis or can be prioritized based on the individual’s birthdate, level of need, whether the individual is in transition or other indicators of urgent medical or social need.

As of 2015, there are more than 428,000 people with I/DD across the country on Medicaid waiver waiting lists.

This is especially troubling considering that more than 70 percent of people with I/DD live at home with a family member, many of whom are aging and may soon need long-term care themselves.

Securing a spot on a waiting list is one thing; tracking your status is quite another.

“To get on waiting lists, individuals typically go through a process to determine eligibility,” Kennis said. “This is usually done at the state or local level. After being determined eligible for services, individuals may or may not have to go on a waiting list depending on the state’s process and the availability of funding.”

However, some states do not determine eligibility until a waiver slot becomes available. In other words, not all people on waiting lists may even be eligible for Medicaid waiver coverage.

As of 2015, 61 percent of waiting lists for HCBS waivers screen for eligibility at the time of waiting list enrollment.

After taking a ticket, so to speak, frustration often builds as people inquire about their status. Individuals on waiver waiting lists cannot necessarily foresee when a waiver slot will open up or if they will move smoothly from the waiting list to occupy a waiver slot.

People coming off the waiting list is more based on available funding, not on people leaving services.

To bid farewell to waiting lists, funding is vital.

“It would be difficult to completely eliminate the list, for two reasons,” Kennis said. “One is there’s not enough funding. Two, providers don’t have the capacity to provide services to everyone because of the staffing crisis. Even if the money was there, you still have to hire people to provide these services.”

“It’s an ongoing issue, that’s for sure,” she added. “It seems like it’s getting worse as funding gets tighter and tighter.”

Additional sources: